Manufacturers’ efforts to avoid microbial contamination are complemented by developments from bioprocessing suppliers. We list novel solutions and ways of working to help beat bioburden.

Sharing bioburden challenges

A multi-faceted, collaborative approach is the key to addressing the multiple challenges of bioburden control. Improved ways of working in the manufacturing facility have been facilitated by supplier developments in automation, closed systems, and single-use solutions. Similarly, progress in straight-through processing and continuous processing is supported by joint projects. Another important area where suppliers can contribute is around sanitization and storage procedures for protein A chromatography resins, widely used to purify mAbs (1).

Single-use solutions

The introduction of single-use solutions has in many ways simplified bioburden control. Products are usually delivered presanitized, eliminating procedures and validation work. With single-use solutions, upstream and downstream processing can be done in the same “ballroom”-style facility with high bioburden control and great flexibility as products, unit operations, and scales of production change over time.

Column operation and closed handling

Chromatography column packing and unpacking would normally introduce a bioburden risk. Systems now exist that address this challenging workflow. The whole process becomes much less “hands-on”, more reproducible, and essentially a closed operation, apart from the initial transfer of resin from its transport container. Automated column handling combined with innovative equipment design features enable high standards of hygiene to be established and maintained (2).

Buffer preparation

The volumes and numbers of buffers in downstream processes are often considerable and manual preparation of these buffers is a bioburden risk. With in-line conditioning, buffers are prepared automatically, at point of use, from concentrated stock solutions of acidic and basic buffer components together with water for injection (WFI). This simplifies buffer preparation and clearly minimizes manual operations, as well as reducing buffer tanks and floor space. It is a more accurate and reproducible way to prepare buffers than simple dilution (2).

Furthermore, premade stock solutions, sterile filtered into gamma-irradiated single-use bags, are available from suppliers to further streamline buffer preparation and provide opportunities for better bioburden control.

Sanitization

Sanitization is a necessary procedure in a production process where unit operations, like chromatography, are operated over many cycles. Experience has resulted in 1 M NaOH becoming the backbone of most sanitization procedures, due to efficacy and low cost as well as ease of detection, removal, and disposal. For chromatography resins with protein ligands that are sensitive to high pH conditions, lower concentrations of NaOH or alternative cleaning and sanitization solutions have to be used.

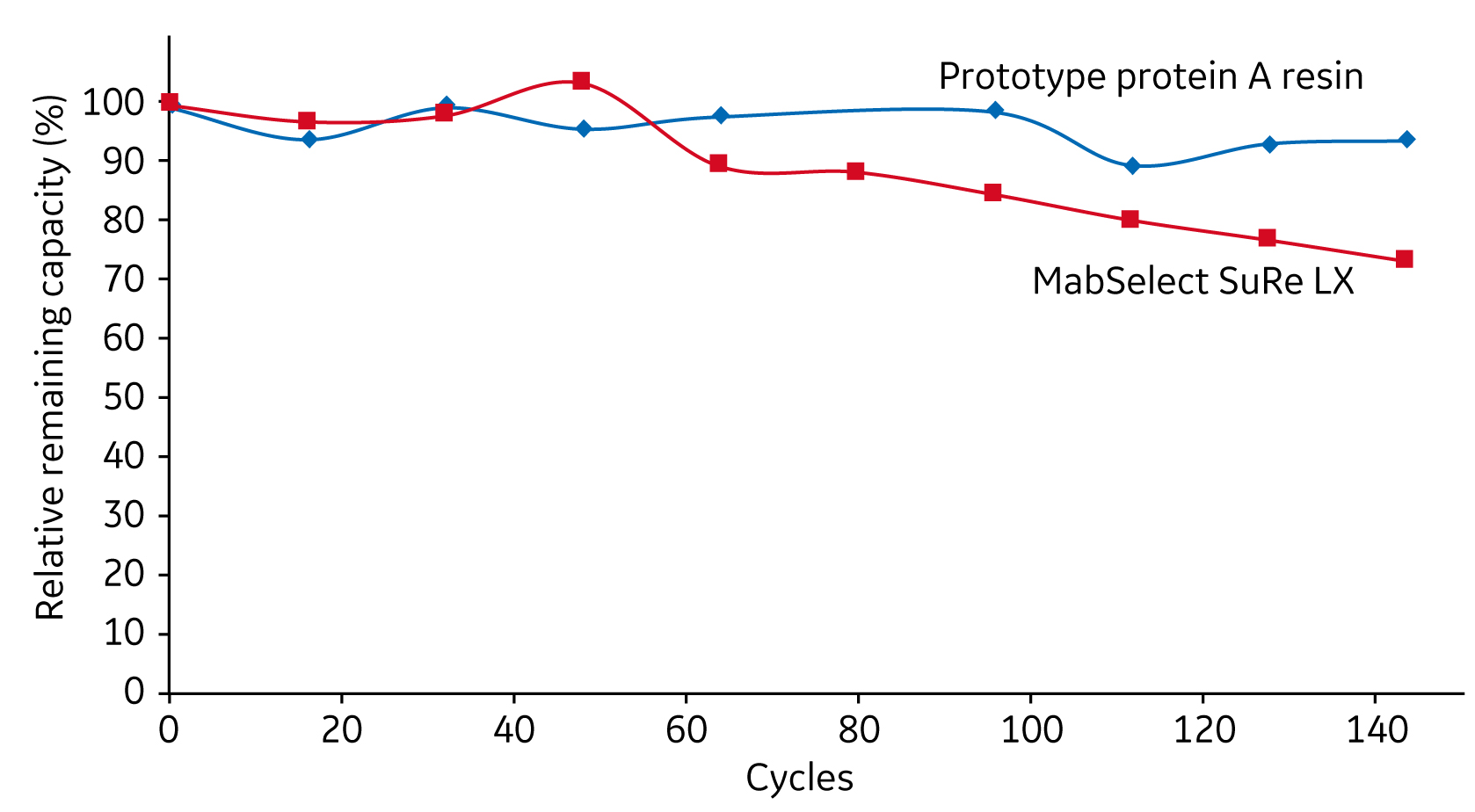

For protein A resins, widely used to purify mAbs, genetic engineering has been applied to improve alkali stability as demonstrated with MabSelect SuRe and MabSelect SuRe LX (3). Continued engineering of the protein A ligand indicates that further improvement in alkali stability is possible (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Improved alkali stability of genetically engineered protein A ligands. This shows two protein A resins packed in columns, exposed to 140 × 15 min cycles of 0.5 M NaOH, and tested for IgG binding.

Storage

Storage of equipment and consumables also introduces a risk for microbial growth. Chromatography resins should be stored in bacteriostatic solutions that are non-toxic to humans, inexpensive, and easy to dispose of. A crucial property is the long-term stability of the chromatography resin, and here suppliers can contribute with studies and recommendations (4).

Spore-forming bacteria and the sanitization of resins

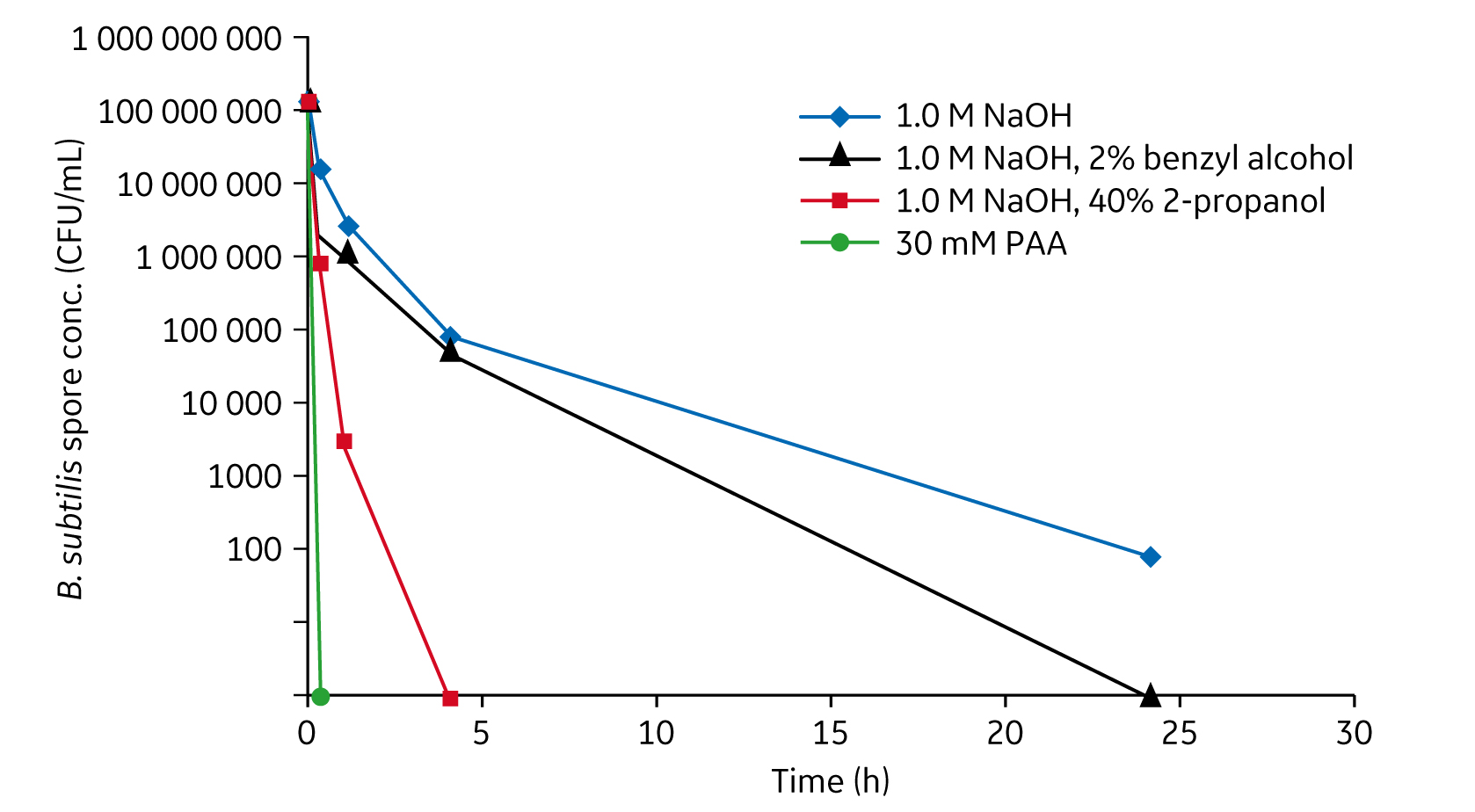

Spore-forming bacteria, like Gram-positive Bacillus subtilis (B. subtilis), are difficult to eliminate because of their resistance to high concentrations of NaOH. A study performed at GE Healthcare shows that treating a 50% slurry of MabSelect SuRe with 20 mM peracetic acid (PAA) gives greater than 6-log reduction of B. subtilis spores within 30 min (Fig 2). Treatment with 20 mM PAA for 30 min or 30 mM PAA for 15 min could be used without significantly affecting mAb recovery or purification performance of the resin (5).

The frequency of PAA treatments should be determined specifically for each mAb process, because extended exposure will reduce the binding capacity of the MabSelect SuRe resin. As a general rule, sanitization with 20 to 30 mM PAA according to recommendations above can be performed two to three times during the lifetime of a MabSelect SuRe resin. For example, sanitization can be appropriate after column packing or after storage, as well as in case of a bioburden incident.

Fig 2. B. subtilis spore kill kinetics of various sanitization agents in 50% MabSelect SuRe resin slurry. 30 and 20 mM PAA are sporicidal with contact times of 15 to 30 min.

Learn more about bioburden control strategies

Bioburden control requires constant vigilance on the part of the manufacturer and is supported by developments in automation, closed systems, single-use solutions, raw material quality assurance, and robust approaches to sanitization. Far from being stagnant, exciting innovations are in the works. Read more in a recent white paper on innovations and practices to address microbial contamination.